In the heart of Zimbabwe, a revolutionary architectural project is drawing inspiration from an unlikely source: termite mounds. The Eastgate Centre in Harare, a shopping center and office complex, has become a global icon of sustainable design by mimicking the natural cooling systems of termite hills. Now, this biomimicry principle is being adapted for schools across the country, offering a blueprint for zero-energy buildings in some of the hottest climates on Earth.

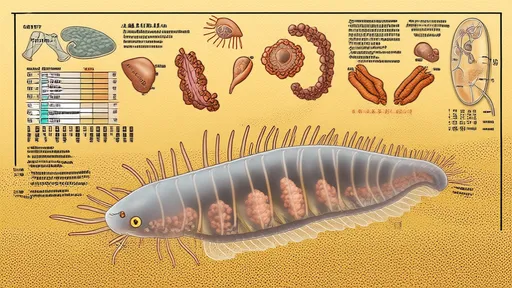

The concept is deceptively simple yet profoundly effective. Termite mounds maintain a stable internal temperature despite extreme external heat through a network of vents and tunnels that allow hot air to rise and escape while drawing in cooler air from below. Architects and engineers studying these structures realized that the same passive cooling principles could be applied to human buildings, eliminating the need for energy-intensive air conditioning systems.

How Termite-Inspired Cooling Works in Schools

At the newly constructed Chiredzi School in southeastern Zimbabwe, the design team created a building that breathes much like its insect-engineered counterpart. The structure features a central chimney that acts as a thermal engine, with strategically placed intake vents at the foundation level. As warm air inside the building rises through the chimney, it creates negative pressure that pulls cooler air through the vents, maintaining comfortable temperatures even when outside temperatures soar above 40°C (104°F).

The walls themselves play a crucial role in the thermal regulation. Made from a special composite of locally sourced clay and other natural materials, they possess high thermal mass - absorbing heat during the day and releasing it slowly at night. This mimics the dense outer walls of termite mounds that protect the interior from temperature fluctuations.

The Educational Benefits of Passive Design

Beyond the obvious energy savings, these termite-inspired schools are proving to have significant educational advantages. Classrooms maintain a stable temperature between 22-26°C (72-79°F) throughout the day, creating ideal learning conditions. Studies have shown that students in these buildings demonstrate better concentration and academic performance compared to those in traditional concrete structures that can become unbearably hot.

Teachers report fewer heat-related health issues among students and staff. "Before, we would have children fainting during afternoon classes," explains Mrs. Moyo, a teacher at Chiredzi. "Now, the children are alert and engaged throughout the school day. Even our textbooks last longer because the humidity is better controlled."

Economic and Environmental Impact

The financial implications of this design approach are transformative for Zimbabwe's education system. Without the need for conventional air conditioning, schools save approximately 90% on energy costs - critical savings in a country where many rural schools struggle with basic infrastructure funding. Maintenance costs are similarly reduced as the passive systems have no moving parts to repair or replace.

From an environmental perspective, each termite-inspired school saves an estimated 30 tons of CO2 emissions annually compared to conventionally cooled buildings. As the program expands to more schools across Zimbabwe, the cumulative impact could significantly contribute to the country's climate change mitigation efforts.

Challenges and Adaptations

Implementing this innovative design hasn't been without challenges. Early prototypes struggled with dust infiltration through the ventilation system - a problem termites solve with precisely angled entrance tunnels. Architects addressed this by incorporating fine mesh filters and adjusting vent angles based on prevailing wind patterns.

Another adaptation involved modifying the traditional thatched roof design common in Zimbabwean architecture. While aesthetically pleasing and culturally appropriate, thatch proved less effective for the chimney effect. The solution was a hybrid design combining thatch's insulating properties with strategic metal components to enhance airflow.

Scaling Up the Solution

The success of initial pilot schools has led to government support for expanding the program. Zimbabwe's Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education has incorporated termite-inspired design principles into its national school construction guidelines. International organizations have taken notice too, with UNESCO considering the model for application in other hot climate regions across Africa and beyond.

Local communities have embraced the concept, with many parents volunteering labor for school construction once they understand the long-term benefits. "We used to think modern buildings needed glass and air conditioners," comments a village elder involved in one project. "Now we see that the answers were right here in our land all along, in the mounds the termites build."

The Future of Biomimetic Architecture

Zimbabwe's termite-inspired schools represent more than just an energy-efficient building solution. They demonstrate how looking to nature's time-tested designs can provide answers to some of our most pressing modern challenges. As climate change makes cooling needs more acute, especially in developing countries, such biomimetic approaches offer sustainable, affordable alternatives to energy-intensive technologies.

Research teams are now studying other aspects of termite mound engineering, including their remarkable structural integrity and flood resistance. The humble termite, often considered a pest, may ultimately provide multiple solutions for sustainable living in a warming world.

For Zimbabwe's students, the benefits are already tangible. In classrooms that stay cool without electricity, using designs borrowed from nature's own engineers, a new generation is learning not just traditional subjects, but valuable lessons about living in harmony with their environment.

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025