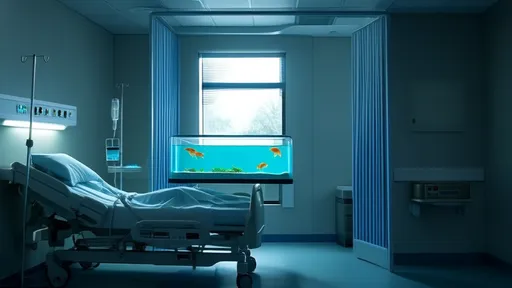

The hushed beeps of cardiac monitors and the rhythmic whoosh of ventilators create an oddly sterile symphony in intensive care units. Yet beneath this clinical cadence lies an undercurrent of human distress - the palpable anxiety gripping patients tethered to tubes and machines. For decades, clinicians have sought ways to ease this suffering without resorting to additional pharmaceuticals. An unexpected solution has emerged from an ancient source: water. Not as medicine, but as medium - specifically, the carefully curated aquatic ecosystems found in aquariums.

Recent studies reveal what marine biologists have long understood intuitively - that observing aquatic life exerts a measurable calming effect on the human nervous system. The phenomenon, termed aquarium sedation effect, demonstrates significant reductions in cortisol levels and sympathetic nervous system arousal when subjects view thriving aquarium environments. ICU patients experiencing this intervention show marked decreases in respiratory rates and blood pressure fluctuations compared to control groups.

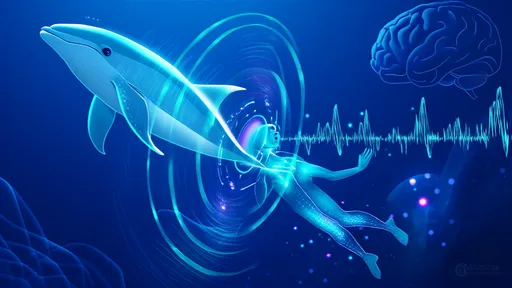

Dr. Eleanor Voss, lead researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital's Center for Environmental Therapeutics, explains: "The visual complexity of aquatic environments appears to engage our parasympathetic nervous system in ways that urban landscapes or even terrestrial nature scenes cannot match. There's something neurologically primal about water's movement and the darting patterns of fish that bypasses our conscious cognition to directly soothe limbic system distress." Her team's fMRI studies show decreased amygdala activity within minutes of aquarium exposure.

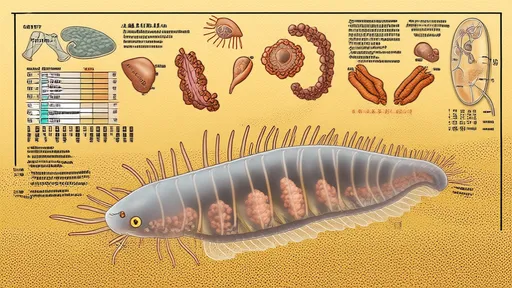

The therapeutic mechanism operates on multiple physiological levels. The shimmering refraction of light through water creates naturally occurring fractal patterns that entrain brainwaves toward alpha states. Fish movement follows mathematical sequences similar to those found in relaxing visual white noise. Even the sound of bubbling filtration systems masks alarming hospital noises while providing a consistent auditory rhythm. Together, these elements create what neurologists call a sensory cocoon - an environment that buffers against overstimulation.

Practical implementation in ICUs requires careful consideration. Standard aquariums prove impractical due to space constraints and infection control protocols. Innovative solutions include wall-mounted, self-contained ecosystems with antimicrobial coatings and virtual reality alternatives for immunocompromised patients. The most effective designs incorporate biodiversity - a mix of plant life, schooling fish, and solitary species moving at varying speeds to create visual interest without overwhelming complexity.

Nursing staff report ancillary benefits beyond patient outcomes. "It changes the entire atmosphere of the unit," observes ICU charge nurse Marcus Chen. "Families congregate around the tanks, having different conversations than they do at the bedside. Staff take micro-breaks watching the fish. There's this unspoken understanding that we're all benefiting from this shared oasis." Some hospitals have documented reduced staff burnout rates in units incorporating aquatic features.

Critics initially raised concerns about cost and maintenance, but modern systems have addressed these issues. LED lighting and advanced filtration make contemporary therapeutic aquariums far more energy-efficient than their household counterparts. Many institutions partner with local marine biology programs for maintenance, creating educational opportunities while controlling expenses. The return on investment becomes clear when considering reduced sedative costs and shorter ICU stays associated with the intervention.

Perhaps most remarkably, the benefits appear universal across demographic lines. Unlike music or art therapy - where cultural preferences significantly impact effectiveness - water's appeal seems to transcend personal background. From octogenarian cardiac patients to pediatric trauma victims, the response patterns remain consistently positive. This biological universality suggests we're tapping into something evolutionarily ancient, a hardwired connection between Homo sapiens and aquatic environments that predates civilization itself.

As healthcare continues its shift toward more holistic models, non-pharmacological interventions like aquarium therapy gain credibility. What began as anecdotal observations about patients seeming calmer near waiting room fish tanks has blossomed into a legitimate field of environmental medicine. Research now explores applications beyond ICUs - from chemotherapy suites to dementia care facilities. The water that covers most of our planet may hold one of the gentlest keys to healing the mind-body distress of critical illness.

The implications extend beyond clinical settings. In an age of digital overload and urban stress, the aquarium effect offers a blueprint for designing calming spaces wherever people face anxiety. Architects now incorporate aquatic elements into everything from airport lounges to corporate wellness rooms. Yet nowhere does this intervention feel more vital than in the high-stakes environment of intensive care, where a glimpse of darting neon tetras might mean the difference between panic and peace for someone fighting for their life.

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025