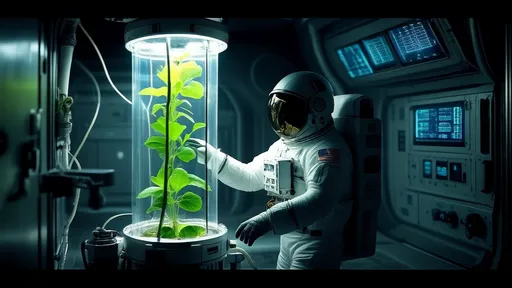

Inside the sterile white corridors of the International Space Station, a revolution is quietly taking place. It doesn’t involve rocket thrusters or solar arrays, but something far more terrestrial in origin—vegetables. The Vegetable Production System, affectionately dubbed "Veggie" by astronauts, has become an unexpected protagonist in humanity’s off-world narrative. This isn’t just about fresh salads in zero gravity; it’s a critical step toward long-duration spaceflight and extraterrestrial colonization.

NASA’s Veggie unit, a compact growth chamber about the size of a carry-on suitcase, has been hosting an array of leafy greens since its 2014 debut. The system uses LED lights to simulate sunlight, with a mix of red, blue, and green spectra tailored to plant photosynthesis. But growing food in microgravity isn’t as simple as replicating Earth’s conditions. Without gravity, roots don’t naturally orient downward, water doesn’t drain, and air circulation becomes a puzzle. Early attempts saw plants drowning in their own humidity or growing in erratic, tangled masses.

One breakthrough came with the development of "plant pillows"—small bags containing a clay-based growth medium and fertilizer. These pillows, which look like oversized tea bags, provide structure for roots and regulate moisture. Astronauts inject water into them using syringes, a far cry from the sprinklers of terrestrial farms. The pillows also mitigate another space oddity: in microgravity, roots sometimes grow upward, emerging from the soil like alien tendrils. By containing the growth medium, the pillows keep the experiment (and the station) tidy.

The psychological impact of tending plants in space cannot be overstated. Astronauts who spend months confined to the station’s metallic hull often speak of Veggie duty as a highlight. There’s an almost sacred ritual to checking seedlings each morning under the pink glow of LEDs. "You forget what green looks like up here," remarked one crew member during a downlink interview. The scent of fresh growth—a rarity in the HEPA-filtered air—triggers visceral memories of Earth. This emotional resonance is so pronounced that NASA now considers space gardening a form of therapy for crews on extended missions.

Scientific curiosity extends beyond lettuce and zinnias (the first flower grown in space). Recent experiments involve dwarf wheat and transgenic crops engineered for space’s unique stressors. Some plants are modified to fluoresce under stress, creating a visible alert system for suboptimal growing conditions. Others have enhanced antioxidant production to combat space radiation’s effects. The most ambitious projects aim to create closed-loop systems where plants recycle astronauts’ exhaled carbon dioxide and bodily waste into food—a self-sustaining micro-ecosystem for missions to Mars.

Data from these cosmic gardens is reshaping agricultural science back on Earth. The precise control over light spectra, humidity, and nutrients has led to breakthroughs in vertical farming technologies. Urban growers are adopting space-derived LED recipes to boost basil yields, while drought-stricken regions study the water-efficient "space hydroponics" techniques. Ironically, the technology developed to feed astronauts may one day help feed populations in Earth’s most inhospitable regions.

Yet challenges persist. Pollination in microgravity remains an unsolved riddle—bees don’t do well in space, and manual pollination of fruiting plants like tomatoes is labor-intensive. Then there’s the enigma of "space flavor": multiple crews report that crops like space-grown lettuce taste "weaker" or "metallic," possibly due to altered volatile compound production in microgravity. Food scientists are now developing "space seasoning" profiles to compensate for this sensory deficit.

The logs from these orbital gardens read like a cross between a botanist’s field notes and a sci-fi novel. Entries detail how mustard seedlings performed a slow-motion dance toward the LEDs in the absence of gravity cues, or how a single rogue pea took over an entire growth tray in what crew dubbed "The Invasion of the Space Pea." These anecdotes underscore a profound truth: wherever humans go, we bring life with us—not just as sustenance, but as a living connection to the planet we call home.

Looking ahead, the Veggie program will expand to include larger growth chambers in upcoming space stations and lunar habitats. The lessons learned—from root orientation to crew psychology—will directly inform designs for Martian greenhouses. Perhaps future colonists will look back at these early space farming logs the way we study ancient agricultural manuscripts: as the first fragile steps toward becoming a multiplanetary species. For now, each crisp leaf harvested in orbit represents a small but tangible victory in the grand challenge of living beyond Earth.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025