In the shadowy corridors of history, countless mysteries remain unsolved—murders lost to time, identities erased by centuries, and civilizations vanished without explanation. But now, a revolutionary field is breathing new life into cold cases that are hundreds or even thousands of years old. Ancient DNA forensics, a cutting-edge intersection of archaeology, genetics, and criminal investigation, is cracking historical enigmas one genome at a time.

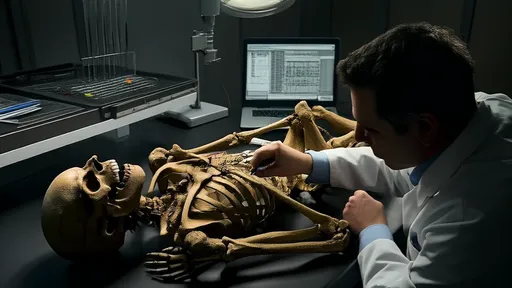

The journey begins with skeletal remains—fragments of bone or teeth preserved in tombs, bogs, or permafrost. These unassuming relics hold within them a treasure trove of genetic material, waiting to reveal secrets long buried. Unlike traditional archaeology, which relies on artifacts and written records, paleogenetics delves directly into the biological blueprint of the past. By extracting and sequencing ancient DNA (aDNA), scientists can reconstruct everything from an individual’s ancestry and physical traits to the diseases that plagued them.

One of the most striking applications of this technology is in solving historical crimes. Take, for instance, the infamous "Vampire of Venice," a 16th-century woman buried with a brick forced into her mouth—a ritual meant to prevent her from rising as the undead. When researchers analyzed her DNA, they found genetic evidence of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for the Black Death. The woman wasn’t a vampire; she was a plague victim, feared and misunderstood by her community. Her remains, once a symbol of superstition, now stand as a testament to how disease shaped human behavior.

But ancient DNA isn’t just about correcting misconceptions—it’s also about justice. In 2017, geneticists helped identify the remains of King Richard III, the last Plantagenet king of England, beneath a parking lot in Leicester. His skeleton bore the brutal marks of battle, including a cleaved skull and a curved spine. DNA extracted from his bones confirmed his identity by matching with living descendants, closing a 500-year-old missing persons case. For historians, it was a revelation; for forensic scientists, it was proof that even medieval cold cases could be cracked.

The challenges, however, are immense. Ancient DNA is often degraded, contaminated, or fragmented, requiring painstaking laboratory techniques to piece together. Researchers must work in sterile environments to avoid modern DNA pollution, and even then, success isn’t guaranteed. Yet, when the strands of genetic code finally align, the results can rewrite history. In 2021, aDNA analysis revealed that the victims of the Salem witch trials weren’t, as long assumed, all women. One of the accused—a man named Giles Corey—was genetically confirmed among the remains, shedding new light on the gender dynamics of the hysteria.

Beyond individual cases, ancient DNA is unraveling broader historical puzzles. The disappearance of the Neanderthals, once attributed solely to competition with Homo sapiens, now appears more complex. Genetic evidence shows interbreeding between the species, suggesting a nuanced relationship rather than outright warfare. Similarly, the colonization of the Americas is being revisited thanks to aDNA from pre-Columbian remains, which reveals waves of migration previously undocumented.

Ethical questions linger, of course. Who has the right to excavate and analyze the dead? How should indigenous communities be involved in studies of their ancestors? These debates are as much a part of ancient DNA forensics as the science itself. Yet, the field’s potential is undeniable. From exonerating the wrongly accused of medieval Europe to tracing the spread of ancient pandemics, genetic archaeology is proving that the past isn’t as distant as we think.

As laboratories continue to refine their techniques, the next decade promises even more breakthroughs. Imagine identifying the unknown soldiers of the Crusades, or pinpointing the origins of the Black Death’s Patient Zero. With each genome sequenced, the dead speak a little louder—and history’s coldest cases grow warmer.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025